(edit 22nd August 2018 – readers may also be interested in the careers of Ana Olgica and Amity Cadet)

https://open.spotify.com/embed/user/aoifenichorcorain/playlist/74KqlNzk7NMTChonWbOC75

Continuing from my profiles of the work of Amity Cadet and Ana Olgica , I thought I would focus on another artist, once legendary, now only known by a fraction of their life’s work.

Unlike Amity Cadet, there exist some non-Spotify online traces of Aare’s existence, an interview in which he refutes the absurd and insulting thesis that he does not exist, that he is some kind of “fake artist.” Aare articulates a purist approach to a musical career in the age of streaming playlists:

So the excess trappings of the music industry are social media, websites, CDs, records, and live performances? You take a hard line on this.

EA: I see some of these guys at the farmer’s market selling CDs out of their cars, and I’m like, pfff, this guy is a sellout, a complete fraud. I knew this one guy in college who made a tape and spent, I don’t know, an hour designing a cover for it? With a band photograph and a logo? And he listed his email address on the back? Like, ooh, I’m so important I think people should email me. Man, I just shake my head. What a waste of energy.

CP: And so the only appropriate venue for music is a Spotify playlist?

EA: Basically. Yeah, when you get down to it. Put me on a playlist, and that’s all I need. That’s music in its purest form. I never even considered putting my music online anywhere, but these Spotify curators are just relentless in their pursuit of creating the best playlists. I was so stupid I didn’t even know you could “curate” music – I thought that was like an art thing. But when they told me my four songs could exist in a free-floating, context-less, non-corporeal environment for the benefit of people falling asleep with their earbuds in, I couldn’t say no. I told them, “This is what I’ve been waiting for. This is my moment. Sign me up.”

Unlike Amity Cadet, however, Enno Aare is represeneted on Spotify by not one, but four works. On YouTube we find three:

In my previous posts I showed how Amity Cadet and Ana Olgica were both profound, emblematic artists, whose presence on playlists entitled “Classical Chillout” and such may mask their visionary artistrry. A hint to the importance of Eeno Aare comes in the interview linked to above – the phrase “for the benefit of people falling asleep with their earbuds in.” For Eeno Aare was a psychonaut, a surfer of the extreme waves of human consciousness, whose surfboard was a piano, and whose Jaws was that most secret, most private act, sleep.

Enno Aare, born in Estonia in 1960, emigrated from the Soviet Union to Israel with his parents in 1975 . They were in Israel only a few months before relocated to Rochester, New York. There Aare’s parents took up roles in The University of Rochester’s Medical School; his mother as a clinical lecturer in anaesthetics, his father as an associate professor in physiology. The Aares both had an academic interest in sleep. They associated themselves with the radical sleep researcher Pietro Corriola. Corriola is one of those figures ignored by the internet , who were highly influential in their day.

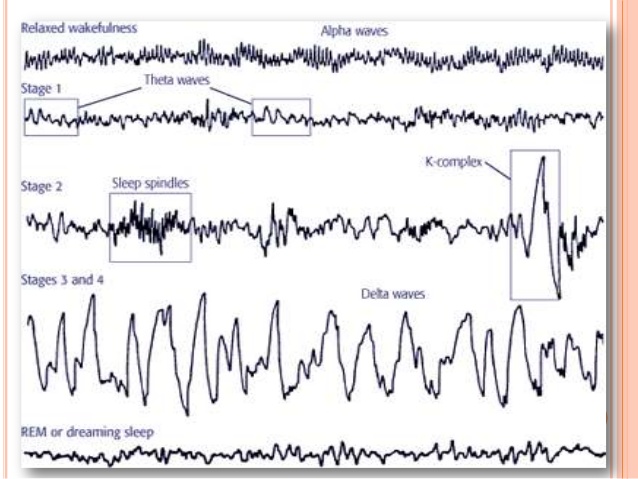

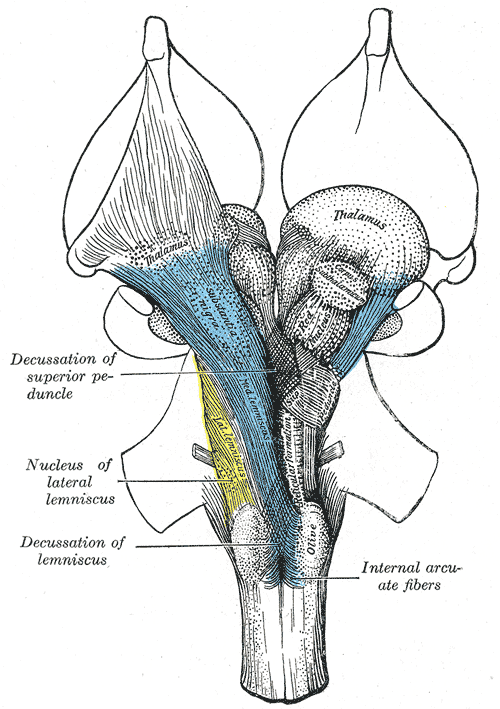

Corriola, born in Ravenna, was based in the Northeast Ohio Medical University Here he devoted himself to whole-hearted opposition to the work of William C Dement and his creation, The American Sleep Disorders Association. Corriola was implacably opposed to Dement’s focus on REM and classifying sleep stages with electroencephalography. Corriola was not opposed to the physical investigation of sleep per se. Indeed, he proudly identified himself as one of the “Moruzzi school of physiology”. , having trained under the Italian neurophysiologist who connected sleep and wakefulness to the reticular activating system

Despite this, for Corriola,sleep was to be considered metaphysiocally as much as physiologically. Sleep was not to be considered some kind of pathological deviation from normality, but an arena in which the mind floated free of the tyranny of wakefulness. Corriola was horrified by the reductionist approach to dreams and dreaming. For him, the prevalence of sleep disorders was a mass revolt against the medicalisation of sleep.

The Aares enthusiastically took up this cause. In a series of pamphlets, papers, monographs, letters to journals and book chapters they argued for a metaphysical science of sleep which would move beyond a merely neuroscientific paradigm. Corriola, following years of intellectual isolation in the USA (although his ideas had a warmer reception in Europe) was delighted with this sudden upsurge in interest. AS the 1980s dawned, and Corriola’s career entered its twilight, it seemed his legacy was secure. On a April 23rd 1980, this changed.

That day’s edition of the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle revealed that the Aare parents were not in fact doctors of either medicine or physiology. It was implied that their credentials were Soviet forgeries, and the possibility of KGB infiltration was left hanging unspoken

This was officially discounted, although questions were also asked about the rapidity of the Aare’s move from Israel to the USA. In any case, their careers at Rochester were over. Suddenly, 21 year old Enno, freshly graduated Eastman School of Music, was the provider for his parents. He played piano in hotel bars, in wine bars, in cocktail bars, in piano bars, in leather bars, in singles bars, in racetrack bars. He played piano in what non-bar venues he could find work in. He did some work as a session musician. He played on jingles and on children’s TV shows. He played weddings, funerals, Bar Mitzvahs and any other ceremony in which a pianist could conceivably be required.

The 1980s wore on. Enno Aare played piano every day of every week, with no break. He began to despise the world of music, the so called “industry” but also the so called “art.” He began to despise the egotism, the narcissism, the celebration of the self. He recalled his parents’ lofty, idealistic work on sleep – the entry into a purer world, one without the stifling, corroding influence of the ego.

He despised the studio, despised the production of physical recorded music. He dreamt of a way his music could be untethered from the apparatus of the logistics of the industry he despised. He also began working with his parents on ways of using music to ease the passage into the blissful world of sleep. His parents were now spending 20 to 23 hours asleep a day, waking only for some nutrition, hydration, and relief of bodily functions. In a few snatched moments he would show them his music, written in a notation of the family’s own devising, for their approval.

When, years later, the MP3 file ruptured the link between a piece of music and a definite, physical object, Aare took note. This was not quite his dream, as there still was a physical infrastructure required for the file, to be “downloaded” and “shared”, words which captured the inherent physical nature of the file. But it was a start.

It could not be said that Spotify is the complete realisation of Aare’s dream of a pure music untethered by any physical reality, lulling the listener into the world of sleep. For one thing, a physical instrument is still required, and physical apparatus still required to stream the song. It was, however, a significant advance. And, sadly, the day Spotify was launched in Sweden – 23rd April 2006, the twenty-sixth anniversary of the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle story which changed their lives for ever – Eeno Aare’s parents died in their sleep.

nice website, keep on writing.

LikeLike